It was the 1960s, and at Bear Stearns, a fairly young Jerome Kohlberg was looking for a way to help older business owners leave their businesses (without liquidating their life’s work) and recently bereaved families of business owners who were faced with a heavy estate tax burden. The result was the LBO in the form of a “bootstrap” deal developed by securing outside investors, restructuring the companies and floating a private company, often in conjunction with the existing management.

Jerome went on to form one of the most successful investment firms – Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. which in 1988 closed one of the biggest LBO deals in history when it bought RJR Nabisco for $25.1 billion.

The LBO has since then proliferated into a wide range of corporate finance models, including, mergers and acquisitions, takeovers (both hostile and consensual), private equity and start-ups.

Well, LBO is the short version for a leveraged buyout. This is a transaction that is used by companies in order to buy other businesses. The buyout combines the buyer’s equity, together with the debt which is secured via the assets of the target company. The structure of the deal is put together in such a way that the assets from the target company together with its cash flows are used to fund the majority of the financing costs.

And, just for good measure here is the official definition:

Investopedia: “A leveraged buyout (LBO) is the acquisition of another company using a significant amount of borrowed money to meet the cost of acquisition. The assets of the company being acquired are often used as collateral for the loans, along with the assets of the acquiring company. The purpose of leveraged buyouts is to allow companies to make large acquisitions without having to commit a lot of capital.”

There are three elements that must come together for an LBO to happen:

- A sponsor or buyer with an intent to purchase a company

- A company that is the target of the purchaser

- Assets within the company that can be used as leverage

Mike wishes to purchase a car repair garage business from Sal. The price is $50K, but Mike only has $10K. So, Mike, in agreement with Sal, puts up the garage building as collateral for a loan of $40K from the bank. Sal is paid the $50K, and Mike is the new owner of the garage. The garage business now has a $40K debt.

That is an extremely simplified example, but it does highlight an important point – the newly acquired business now has newly acquired debt.

Note:

Most LBOs in the corporate world are entered into with a view to selling the business within a certain number of years. This duration in years is used in LBO calculation models to arrive at various financial projections from the current price to profitability. We shall look at such a model later in this article.

Leveraged Buyout Advantages

For the company buying the business, one of the main advantages of a leveraged acquisition is the equity return. Returns can be increased by leveraging the assets of the seller and by using a capital structure that includes a significant amount of debt.

Of course, there are also advantages for those selling, the main being that LBO is one of the many ways that businesses can be sold. Providing that they are able to exit the businesses at the desired price, then generally most sellers are happy to go along with the LBO process.

For companies that are going through a turnaround or are in distress, LBO could be a viable option. They can enable the business to operate as normal, while the issues are being ameliorated as well as providing the seller with a viable exit.

- Tweet

Leveraged Buyout Disadvantages

For buyers, LBOs can carry some risks. One of the main disadvantages of an LBO is that once completed; a target business can be extremely leveraged – a scenario which allows for only a slight margin of error. Something such as the loss of several key customers could present problems with liquidity, which will then have a knock-on effect and could place the business in serious distress.

There are also some disadvantages for a seller who is executing an LBO. Generally, a buyer will carry out extensive due diligence which can consume both time and resources – both of which could be better spent managing the business.

Additionally, lenders may also opt to carry out their own due diligence – creating even more disruption. Finally, if a key lender doesn’t feel happy with their findings, then the transaction could still fall through – regardless of how much time and effort has been put in.

Many articles on leveraged buyouts pose the following question and for good reason. It is crucial to understand the role of debt within the context of a leveraged buyout.

Is debt good for business or not?

To answer this, we need to understand the effect of leverage.

In Physics, a lever is a mechanical construction that allows the displacement of a large load with smaller (but distributed) effort. In short, a lever amplifies the end result of the initial effort.

Leverage in finance is very much the same. A small amount of capital applied with leverage is used to achieve a return disproportionately larger than without leverage.

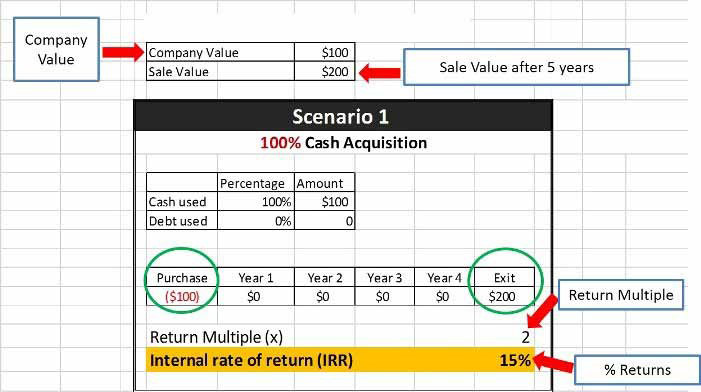

Consider the following acquisition that is made entirely with equity (in this case, cash).

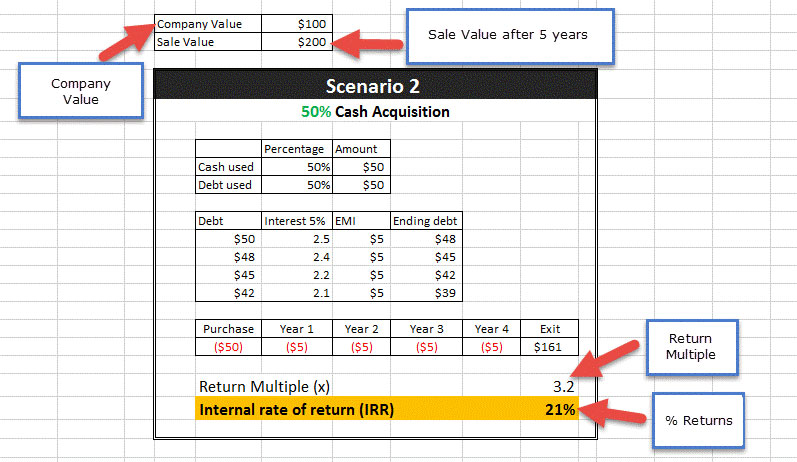

The sale of the company in the above example has generated a return of 15% which is respectable. Next, let’s fund this acquisition with 50% cash and 50% with a loan at 5% interest. The situation now looks like this.

This time around the returns are greater than if the acquisition was made wholly with equity. The figures would be more impressive with a 20/80 equity-to-debt split which is more the industry norm.

This leverage works broadly due to the fortuitous coincidence of these facts:

- Well managed companies usually grow faster than the prevailing interest rates (Most LBO acquisitions undergo some form of restructuring for efficiency)

- The increased investment of equity + debt allows for larger growth of revenue than an investment of just the equity

- Money now (at acquisition) is worth more than money in the future (at sale of a business)

We have now seen that the right level of debt is good for a business. In fact, a business with no debt is probably not generating maximum returns for its shareholders.

Next, let’s have a look at the 6 steps that are involved with LBO analysis:

THE 6 STEPS OF LBO ANALYSIS

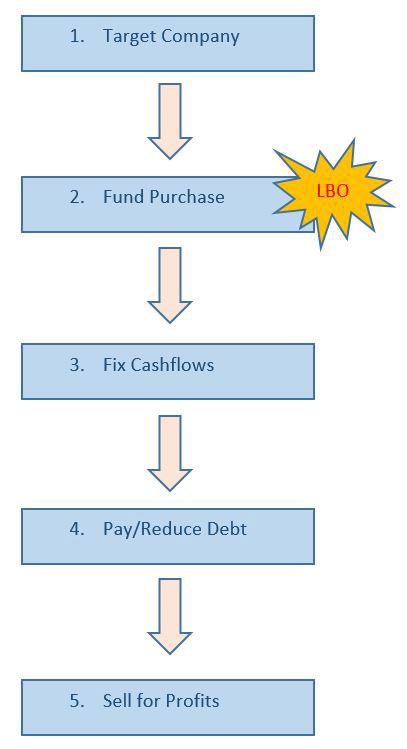

The 5 Steps of an LBO Model

Buying and selling a business broadly consists of these steps. These are fairly self-explanatory, and there are no prizes for guessing where a leveraged buyout can be used. Now each step is a vast subject in itself, but we shall only look in more detail at the first step.

To always focus on the target…

A sponsor is often on the lookout for a particular ‘type’ of company that they wish to acquire. The particular set of attributes defining a desirable target will, in all probability, be unique to the sponsor and the sponsor’s circumstances. But if the sponsor is considering acquiring a target using LBO, then the following attributes become very significant as these can directly affect the acquisition, but more importantly the resale of the company. For most acquisitions, a large chunk of the effort (sometimes the largest) goes into identifying a suitable target.

But what are the attributes of a desirable leveraged buyout target?

Well, a desirable LBO target should have the following:

- Financeable Assets: This is the most important attribute of a target. No assets to collateralise means no leveraged finance and no LBO.

- Company maturity: A mature company is ideal. Sponsors are looking for companies with a proven track record. This translates into an ability to produce returns on the sponsor’s investment (and ability to service debt). Mature companies also have industry standard reasons for wanting to exit. Standard reasons tend to have standard solutions. Start-ups, in contrast, have very little history to fulfill these criteria.

- Cost-Cutting Potential: An efficient company increases the rate of return at resale. One way to maximise returns is to cut non-essential costs.

- Steady Cash-Flows: Again, this is a useful trait if a company is going to pay back debt.

- Low Outstanding Debt: Fits neatly into the LBO model as the company will need to take on debt to finance the deal. On the other hand, if a company is already highly leveraged, but the debt is old, a refinancing may be in order resulting in cheaper and/or lower debt. This is known as recapitalisation as it is a change in the capital structure of the company. A popular variation is a Dividend Recapitalisation, where some money from the financing is paid as a dividend to the shareholders!

- Low future capital expenditure: Maximises returns on investment.

- Feasible Exit: By the end of the holding term, the company must be in good shape to be resold.

And the skillset?

Each of the 5 steps requires a unique set of skills. Larger companies almost always hire experts at each step or involve investment banks who tend to have all the skills in one place. Here is an overview of the skills required at each step.

- Target Companies: Sector Knowledge/Prospecting Experience/Fundamental Analysis

- Funding: LBO Modelling/Debt & Capital Finance Knowledge/Cashflow Analysis/ Balance Sheet Analysis/Investment Banking

- Fix Cashflows+Pay Debt: Financial Engineering/Professional Management (Accounts/Operations etc.)

- Resale: Sector Knowledge/IRR Analysis/Cash on Cash (multiple) Forecasts

What about assets as collateral?

Here are some of the common company assets that can be put up as collateral for financing:

Stock, Buildings, Vehicles, Machinery/Equipment, Accounts Receivable (Invoices/Debt). In some cases, usually for smaller companies, financing can also be obtained against Purchase Orders, but these are not counted as assets.

Finding Assets

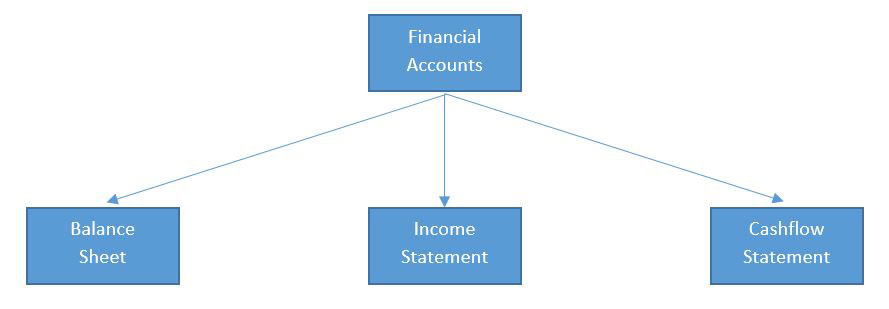

Companies are required to file accounts with the regulatory bodies annually or more often. These are the three statements that form the company’s Financial Accounts.

All figures in all the statements have a story to tell. Some figures are more easily understood while others will need experts to unravel its meaning. A fourth statement usually released by companies is the Additional or Explanatory Notes with each statement. This is not a mandatory or structured document and allows the company to provide a narrative over the accounts. Anomalies, outliers, and deviations are found in these notes where companies try and explain why the numbers are the way they are.

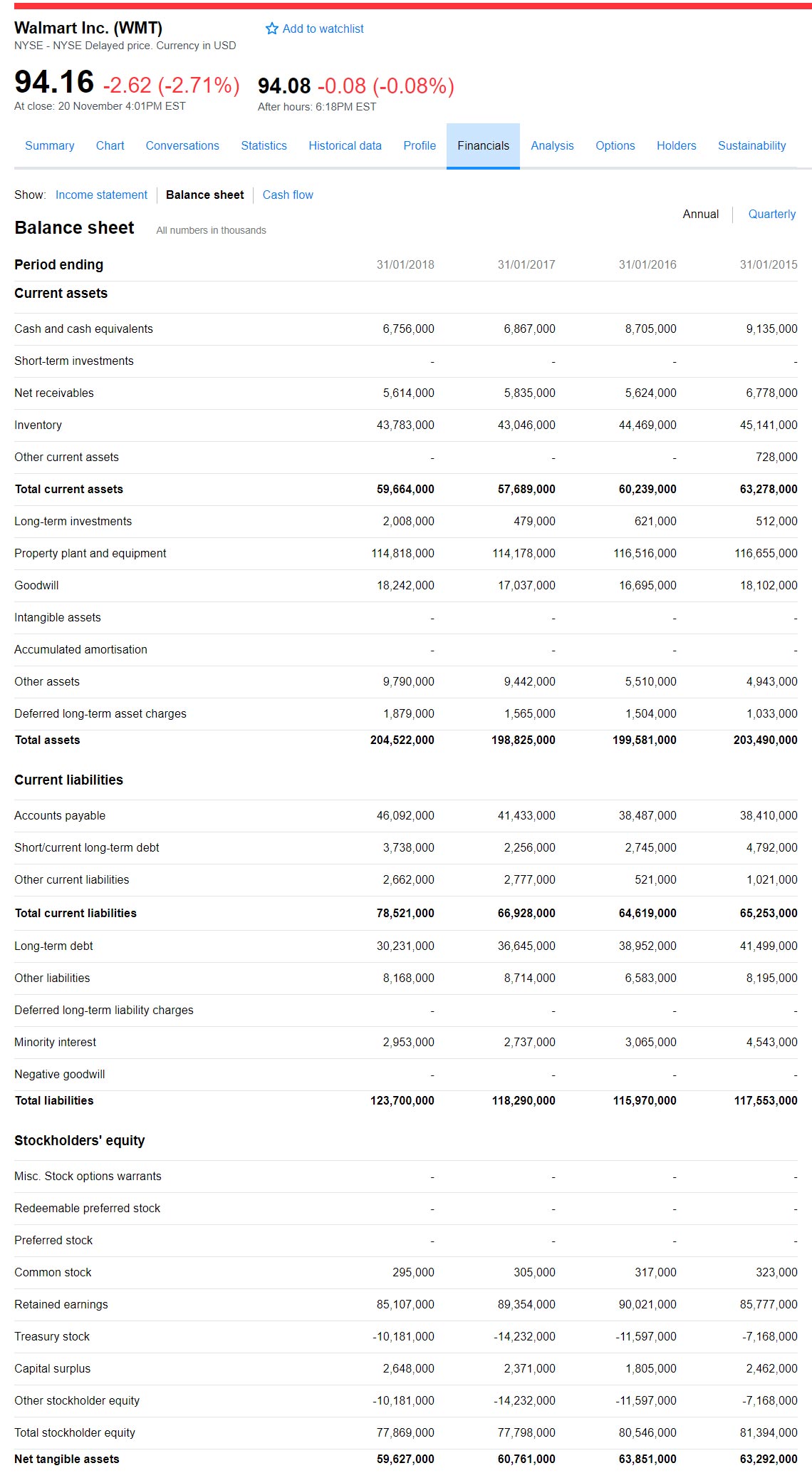

The Balance Sheet

This represents the state of the company’s overall performance based on the accounting equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

This is where the company’s assets will be listed with their current value, along with the liabilities and the shareholder equity. This is a “snapshot” view taken usually at the end of the company’s financial accounting year. For a leveraged buyout, this would be the first place to look for signs of assets that can be used as debt collateral. Long-term debt on the balance sheet indicates the amount of leverage currently in action within the business.

The example illustrated below is Wal-Mart’s balance sheet as at 31st Jan 2018:

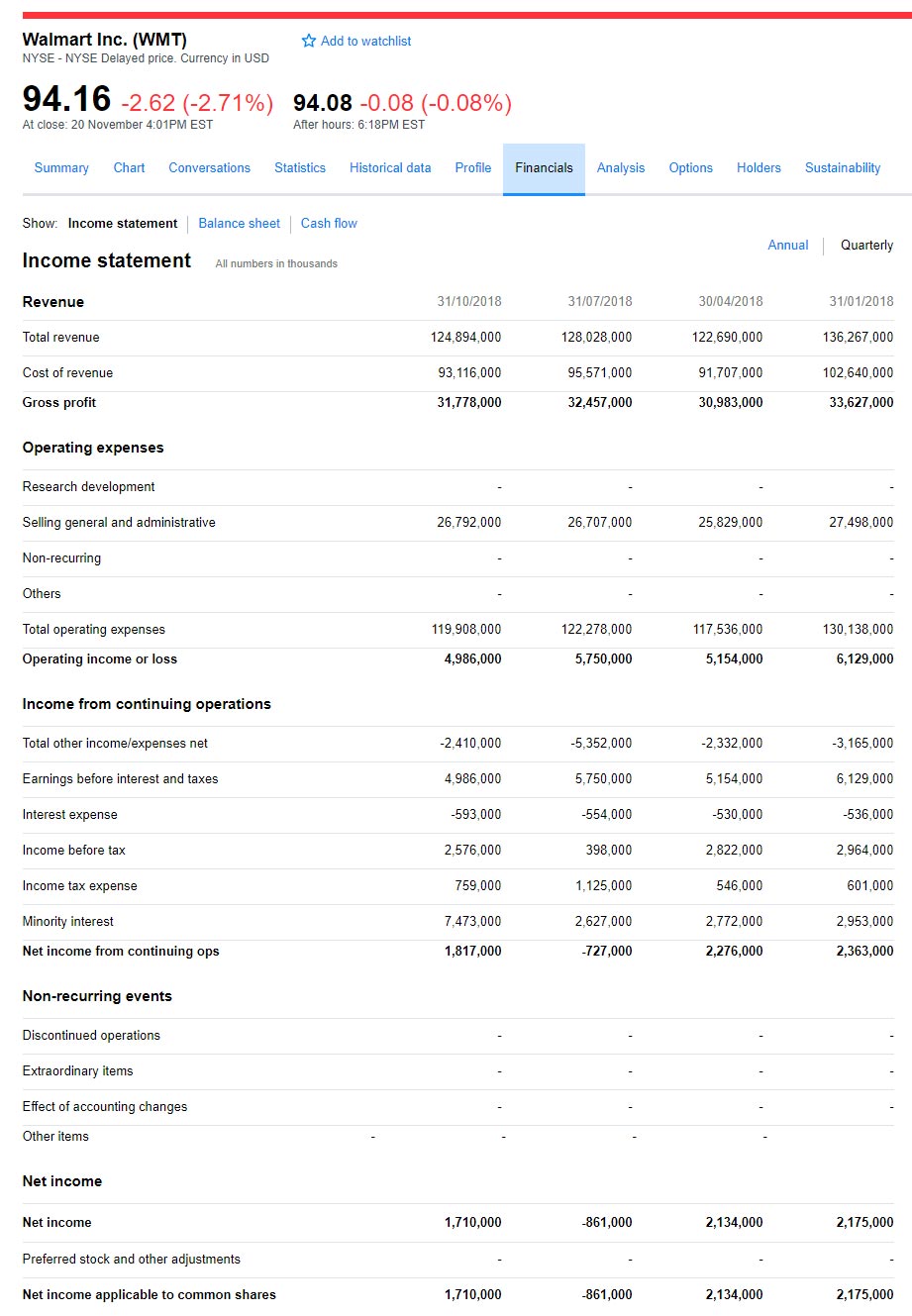

Also known as the Profit and Loss Statement, it represents the company’s performance over a specific accounting period (usually the previous quarter).

It states where the company’s income and expenses have originated. Financial Engineering analysis for checking for inefficiencies in the business would start here.

An interesting section would be the Non-Operating Items. This lists Income and Expenses that are not part of the main business and could hold surprises for leveraged buyout sponsors, pleasant or otherwise.

Illustrated below is Wal-Mart’s current income statement:

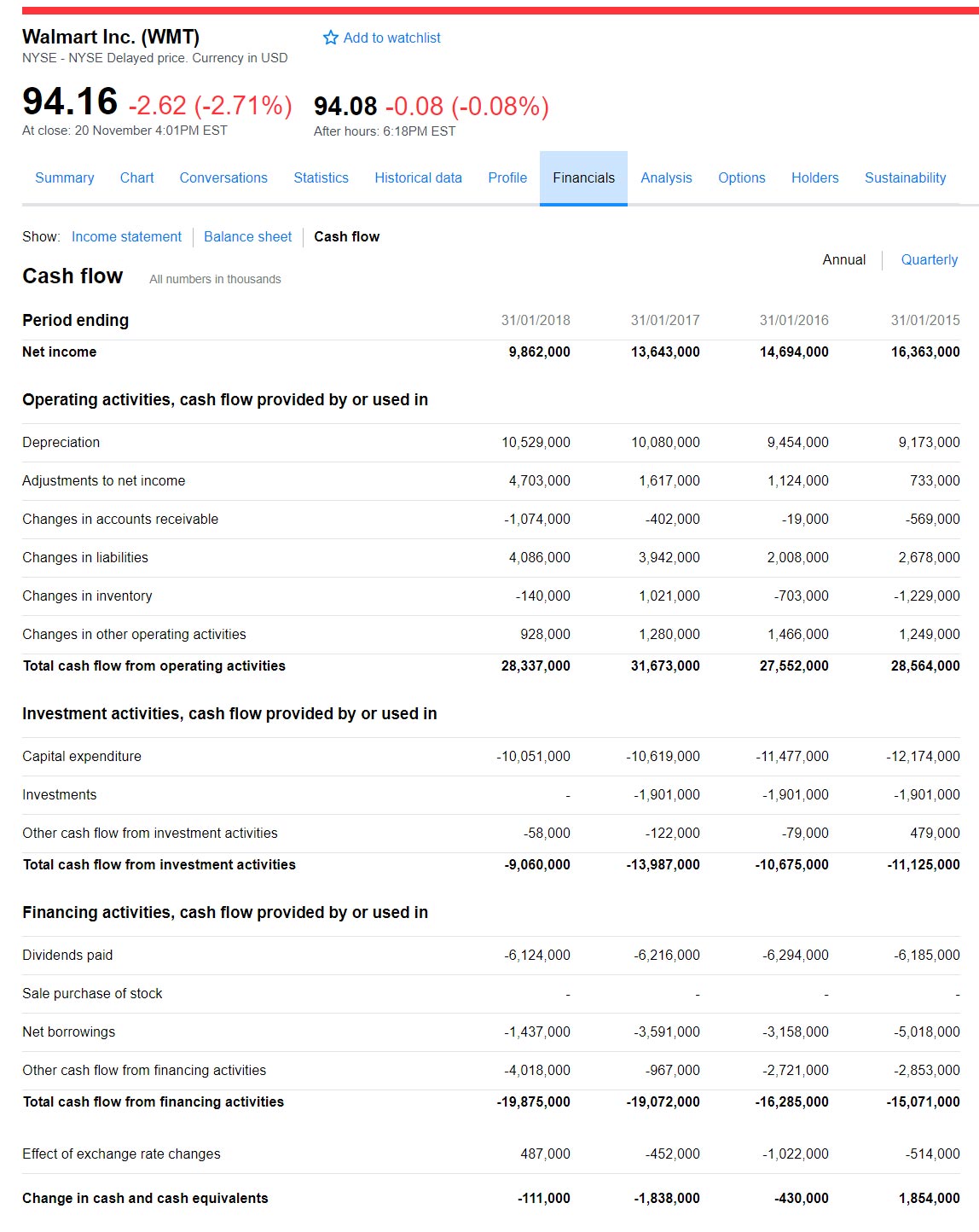

To complete the picture, the statement of cash flow reports the impact of a firm’s operating, investing and financial activities on cash flows over an accounting period.

The cash flow statement shows the following:

- How the company obtains and spends cash

- Why there may be differences between net income and cash flows

- If the company generates enough cash from operations to sustain the business

- If the company generates enough cash to pay off existing debts as they mature

- If the company has enough cash to take advantage of new investment opportunities

This information is key to understanding whether the financials will support the leveraged buyout over the duration of the holding period.

Finally, illustrated below is Wal-Mart’s Cash Flow statement:

A solvency ratio is the key metric which is used to measure the ability of an enterprise in meeting its debts and other obligations. The ratio will give an indication as to whether the cash flow of the company is sufficient enough to meet both long- and short-term liabilities.

- Tweet

Basically, the lower that the solvency ratio is, the higher the possibility that it may default on debt obligations.

Now that we know where to find the figures, we can use them to work out the leverage currently in use. These are known as solvency ratios. They are:

A lower debt ratio usually implies a more stable business with the potential of longevity because a company with a lower ratio also has lower overall debt. Each industry has its own benchmarks for debt, but .5 is a reasonable ratio. This means that the company has twice as many assets as liabilities. Or, this company’s liabilities are only 50 percent of its total assets. Its creditors own half of the company’s assets and the shareholders own the remainder of the assets.

A ratio of 1 means that total liabilities equals total assets. The company would have to sell off all its assets in order to pay off its liabilities. This is a highly leveraged firm, and once its assets are sold off, the business no longer can operate.

With smaller (private) leveraged buyouts, the leverage is up to the new owner and their risk or debt appetite. In some cases, it might be desirable to acquire the company with a high leverage rather than lose it to competitors. This way the new owner can run the company with almost complete autonomy even though the banks might be the major shareholders since banks are usually not interested in running companies.

Understanding Deferred Consideration…

For some businesses, it is not always possible or desirable to obtain a bank loan. This is when deferred consideration may be used. Deferred consideration is when the cost of acquisition is deferred to a future date, i.e., the seller agrees to get paid at a later date. This process evolves into a risk-mitigating act between buyer and seller. The buyer, having paid the seller, faces the risk of dealing with hidden problems within the company. The seller faces the risk of not being paid the agreed deferred amount.

A deferred payment is usually the least risky option for the new owners as there is no third party involved and the previous owner is vested in the performance of the company.

- Tweet

There are many variations of this theme involving:

- Option to split payments – upfront and deferred

- Reducing the initial price in favour of using other options in this list

- Paying interest to the previous owner, effectively taking a loan from them

- Reducing the tax burden for the previous owner

- Performance related incentives (earn-outs) to help sweeten a deferred payment deal

- Retaining previous owners as paid consultants with performance related bonuses

And Personal Guarantees (PGs)

A company being a separate legal entity, defaults on loans by businesses often leave banks with no recourse but to write off the loan as bad debt. Personal guarantees are a bank’s way of holding individuals accountable for defaults. When the assets of a company are not sufficient collateral to finance a loan, the bank asks for personal guarantees from the company executives. The guarantee might also be secured on the personal assets of the executives, e.g., the director’s home.

Leveraged buyouts involving companies with PGs are usually tasked with getting rid of the PG. If the value proposition with the PG is still an attractive one, the PG can be built into the financing of the company. On the other hand, it can be used to discount the price.

Some Personal Guarantee protection is available in the form of insurance.

Listed below is the preferred Strategy for an LBO Deal

- Get the owner to agree HOTs on exclusivity, a notional sale price and timescales for the sale, pending due diligence.

- Assuming due diligence checks out with minor caveats, I would look (very hard) to offer deferred payments out of the cash flow from the business.

- Any initial payments would come from company cash or non-essential liquidable assets.

- Or instead of a down payment, I would offer the owner the option to retain certain assets (e.g., buildings) which the company would lease from the owner, thus, building in an income stream for the owner.

- The next tier would be to seek finance from banks to complete the initial payment, providing cash flow supports the debt + any deferred payments.

- Finally, Joint Venture with partners to provide upfront liquidity.

- Update HOTs with agreed finance structure

- Proceed with the Sale and Purchase Agreement (SPA)

- Completion

- Operate for X years according to LBO model (see section below)

- Exit according to LBO model (see section below)

HOT Structure

Initial HOT Structure:

- Company name/address and other identification

- Seller name/address and other identification

- Buyer name/address and other identification

- Date and place of HOT

- Agreed notional price

- Exclusivity clause

- NDA clause

- Subject to due diligence clause

- Timescales for due diligence with extensions for complications/delays

- Timescales for the offer with extensions for subsequent offers

Additional HOTs after offer agreed with the seller:

- Finance overview with timescales

This would be followed by the legal SPA and SHA (shareholders’ agreement) being signed. It would be ideal to have the Sales and Purchase Agreement drawn up by a single law firm!

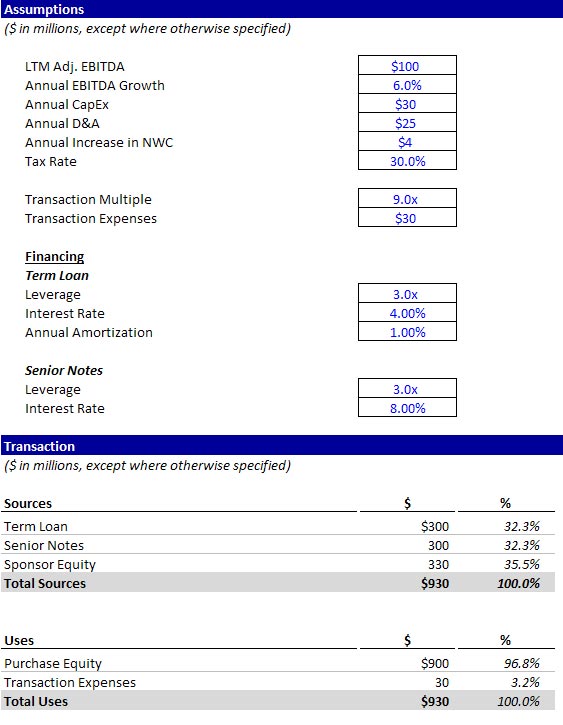

To make things easier, lets’ have a look at the leveraged buyout Modelling example below:

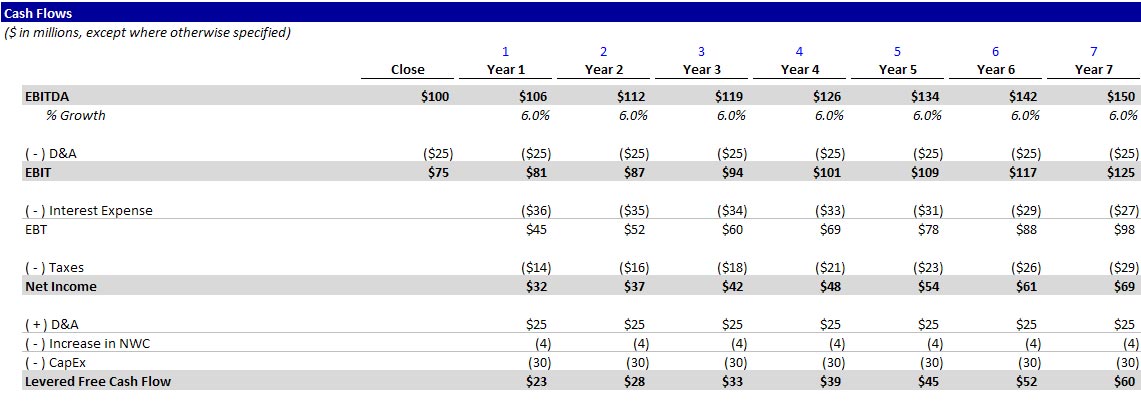

This is an example of a simple LBO model which is used to project the financials over a 7-year term. The objective is to calculate the optimum rate of return and period for which the investment should be held. We make the initial assumptions using available figures for a target company wherever possible. In this example, we have a $100m company valued at 9x EBITDA. The buyer pays $300m, and the rest is raised via a term loan of $300m at 4% interest and another $300m from senior notes at 8% interest.

The first step is to project the cash flow starting from the projected growth and adjusting for interest (calculated in the next section), taxes, depreciation, amortisation, increase in net working capital and capital expenditure. This leaves us with projected free cash flow and shows that the debt can be serviced.

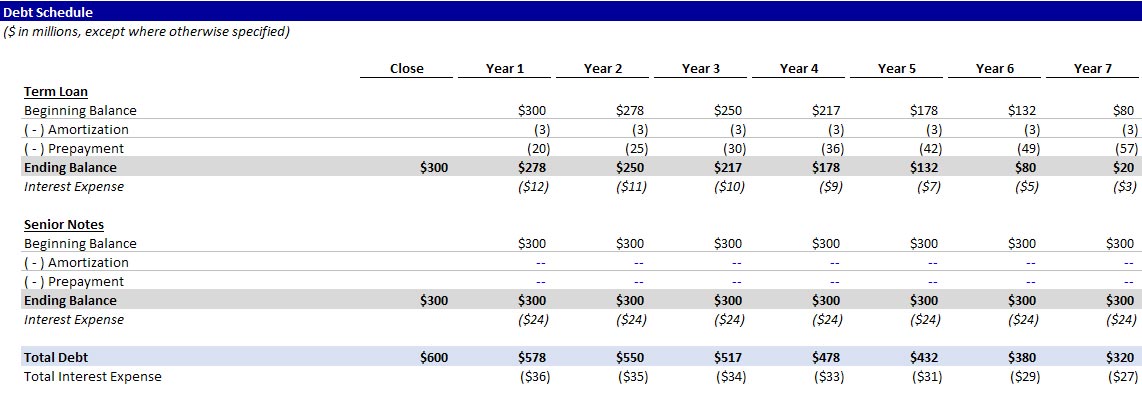

This is a straightforward application of repayment and interest over the 7-year period for the term loan and interest only payments for the senior notes. It also projects the total debt to be repaid in any year if the business were to be sold in that year.

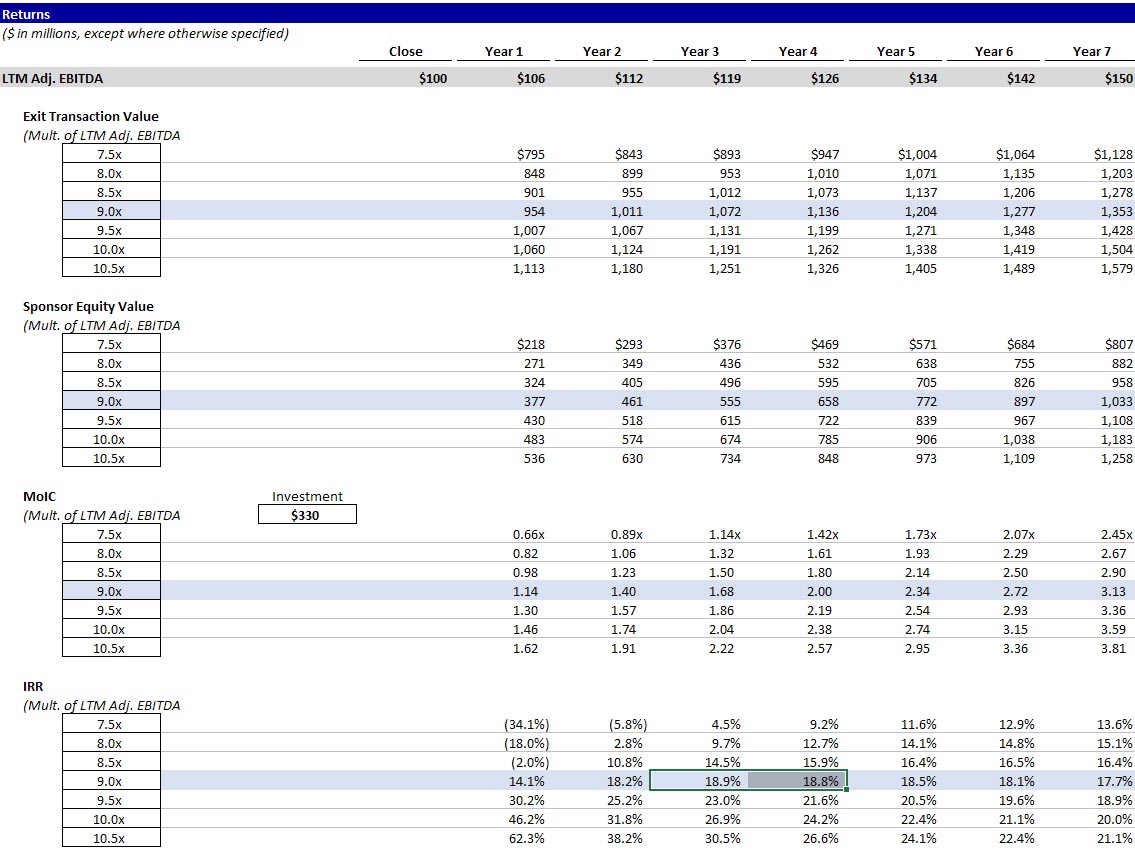

This model illustrates the:

Exit Transaction Value – the exit sale price at different price points (7.5x-10.5x EBITDA) for different years

Sponsor Equity Value – the actual price paid by the new buyer for the business at the various price points

MoIC – the rate of return as a multiple of invested capital

IRR – the internal rate of return as a percentage of capital invested

This model shows that the best outcome for the buyers would be to sell in years 3 or 4 for 9x EBITDA

The bottom line…

For those investors who are lacking equity capital, then leveraged buyout (LBO) can be an extremely fascinating option. They simply borrow money, then invest. I guess the likelihood of a win-win situation will be dependent on the selection process that was used to determine the leveraged buyout candidate, to begin with. For those that have chosen correctly, then there is a high probability of earning huge returns, and for those that don’t – well I think you can guess the rest…

Always keep in mind that the process of applying for an SBA loan can be fairly time consuming and could take the focus away from running the company. Therefore, for some small business owners – more so those that are just beginning – it just might not be worth the time cost.

NOW OVER TO YOU...

Let me know what you think… What is your experience with leveraged buyout (LBO’s)?

Is there anything you would like to share, or you’d like us to cover?

Leave a comment below, and I will be sure to answer as soon as it comes in!!